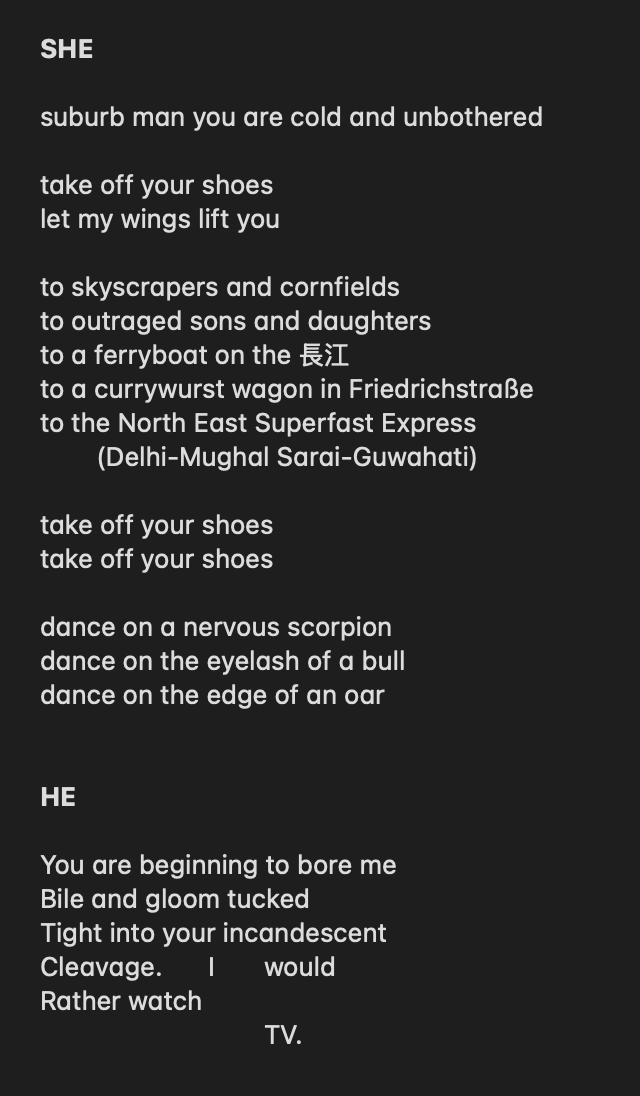

I spoke to my analyst and my goons and they all advised me to begin with a summary. I can dig it. “ADitSoH” traces a dialogue between two characters who are in love. The way it begins is fabulous, in medias res, with “He” saying “There you are / All wonderful and winged and leaking”… we imagine the happy couple lying in bed fiddling with each other’s hair basking in tender afterglow. It’s sort of all down hill from there. “He” is a vulgar caricature of the ‘mature adult’, living in the titular suburbs (of Hell), with a 9-to-5, he watches the weather report, he likes plain shampoos and good strong teas, he orders Thai takeout and drinks beers with his brother. She, meanwhile, is depicted as a sci-fi angel, something between a seraph and a siren, portrayed in visceral realism, the wet dream of a thousand soyfacing infantile tumblr Lovecraft-wannabes. But there will be time to discuss that later. She says she has come to save him from the suburbs of hell. The entire theme of the poem can be summarised in the following exchange (transcribed from the book into my notes app):

There you go. You’ve basically read the book now. The passionate, red-hot free spirit of a fallen angel has taken it upon herself to liberate Flat-Personality Stanley from the chains of his boring life. She showers him in Alanis Morissette platitudes, and he, in all his stupid close-minded self-important boringness, declares that he would rather watch TV and talk to the postman. The difference in personality is clear at the level of style: She is more given to waxing long-winded and verbose, while He expresses himself in short, matter-of-fact statements; She speaks in all lowercase, with internet abbreviations, colloquialisms, and astrology girl-dreaminess, while He follows a rigid and boring style guide and always makes sure to capitalise the first letter of each new line. In the end, it doesn’t work out (at least they didn’t try to save the relationship by having a kid first) and She flutters off in rage, leaving Him to His unscented laundry detergent and smalltalk with the greengrocer.

In particular I find the poem exhibits three tendencies of today’s poetic sensibilities that I cannot stand. The first is a gormless soyfaced obsession with imagery of the mystical, religious, and occult, invoked to manufacture a sense of awe and deep primordiality. The fallen angel archetype in particular (cf. “She”) is one that I cannot stand. It’s a Doctor Who-induced affliction, this character archetype who lives among/interacts with/blends in with mere mortals, but secretly holds deep and awesome power, immortality, otherworldly origins etc. These things are best left to fantasy books written to help unpopular little children get through the day without killing themselves. I think it is your obligation as an adult to accept the banality of your existence.

The second, related phenomenon is the stark contrast of this divine imagery with imagery of the disgusting and visceral. “She”, the glowing fallen angel, recounts how she “washed up / on the oil sluck beaches / of yr shores belly / heaving with the smaller / bellies of fish and birds”. This obsession of mingling divinity with filth is something I originally assumed must be borne of some iconoclastic sensibility, but the more I encounter it, the more I think that isn’t so — I assume we’ve all seen that tumblresque little piece of internet prose describing the birth of Jesus in visceral detail, talking about the screaming mother, the afterbirth, all the muck and the mire, the mother gazing into the slime-covered newborn’s eyes and knowing he’s already fucked? To me that’s the seminal text for this kind of stupid fucking writing, that particular tendency distilled into a short, punchy, widely-circulated internet post. Anyways, that text clearly doesn’t intend to remove the story of the birth of Jesus from divinity; if anything, it seems the author intends to somehow elevate it. That said, I do sort of appreciate the nod to Homer’s sirens, because bitch I love intertext, but the conflation of the gleaming sterile Christian persona of the angel with the gross seabird-like predatory Sirens is yet another symptom of this infantile Tumblr-Lovecraftism.

The final problem I have is the gratuitous and annoying one-dimensional hatred of suburbia. Don’t get me wrong, I am an urban girl through and through. I spent the first 15 years of my life living in suburbs before finally moving to various cities, and let me tell you, I believe that the humanitarian cost of bombing the world’s suburbs into a fine paste with no prior warning is more or less entirely balanced out by the benefits it would bring to the human race. That said, I think if I have to read one more post or book or poem or article whose entire point is “suburbs bad!” I might go entirely berserk. The other book I read on the plane today was Walking through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, the collected writings of Cookie Mueller, published by semiotext(e), the guardians of upper-middlebrow good taste. One of Cookie’s short stories ends with the fabulous soundbite “There is a great art to handling losses with nonchalance”. This goes not only for losses, but any and all things. We have become so prone in our literature to soliloquising and catastrophising and bitching and moaning and engaging in pathetic histrionics when we talk about just about anything we don’t like. We seem to be more concerned with showing everyone how good of a person we are, or how strong our convictions are, than we are about persuasion or commentary, which, as far as the intended purpose of writing goes, are far less autofellatory. More than anything, it’s didactic as shit. To my mind, a far more effective method of writing in critique of things like suburbia in your writing is by very aloofly and nonchalantly presenting the absurdness, or contradictory nature, or violence, or whatever it may be, of the thing that you're trying to criticise. Maybe using well-paced sentence to make it land like a punchline, but beyond that, not drawing too much attention to it, and not abusing your paternalistic authorial role to didactically instruct your reader how they're supposed to feel about it. Frame it in a way that implies your stance, and let the reader draw their own conclusion. It's much wittier. Much more chic. Now, I am somewhat inclined to cut Deborah Levy some slack, as she is not responsible for the British blood which I’m sure played no small part in making her predisposed to morally didactic writing. The English are an irritating and self-righteous people — even their famous self-deprecating humour rests firmly on a bulletproof conviction of their own superiority. And maybe my distaste for this kind of thing comes from my own deeply-engrained attitude of “Don’t fucking tell me what to do”, an attitude very intimately familiar to anyone who has ever made the innocent mistake of trying, out of what is fundamentally a kind and charitable impulse, to give me unsolicited advice. In fairness to Madame Levy, she lets Boring Stanley score a few penalty shots, making decent points about love as a means to seek stability and build a life together. But let’s not kid ourselves — it is abundantly clear whose side the author is on.

In general, this poem reminds me of the posthumous Vale Ave by H.D., primarily because of how I discovered it, what attracted me to it, and why I found it ultimately disappointing. I found Vale Ave in a pile of poetry chapbooks at a bookstore last summer and was instantly very allured by the way it was structured into numbered cantos, a pleasing formal principle and a nod the epics. I find beauty in restraint and structure, an obsession that started with my studies as a music theory student and gradually infected the way I receive all art. In the same way, when I picked up ADitSoH, I was very impressed and excited with the idea of this poetry in conversation, a simple back and forth between HE and SHE, pure dialogue, like a two-hander minus staging. When I finally read Vale Ave I was disappointed by the over the top dramatics and witchy mysticism; as for ADitSoH, I’ve just spent plenty of paragraphs railing on Deborah Levy’s cyber-occultist aesthetics, you don’t need to hear more about it.

Moral of the story is: Walking through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black is a handsome paperback volume of autobiography, short stories, newspaper columns, and essays by Cookie Mueller that you should all read! It’s a fiery window into the life of “a writer, a mother, an outlaw, an actress, a fashion designer, a go-go dancer, a witch doctor, an art-hag, and above all, a goddess.” (John Waters) Chock full of personality, funny, insightful, wistful, and sometimes eulogistic, Clear Water paints a rich portrait of the art scene of New York City, the broader Eastern US and Western Europe in the 1960s-through-80s, including valuable testimonials from the time of the AIDS epidemic. And that’s all I’m going to say about that, because I don’t have anything interesting to say.

-A