The part of the face I've come to think of as "the mask" corresponds roughly to those features represented in abstract in the Venetian cardenio carnival mask: the under-eyes, upper cheeks, temples, lower forehead, brow ridge, and upper portion of the nose. There is a stark, rugged, yet organic beauty in these forms and the way they work together to form the structure of the upper face.

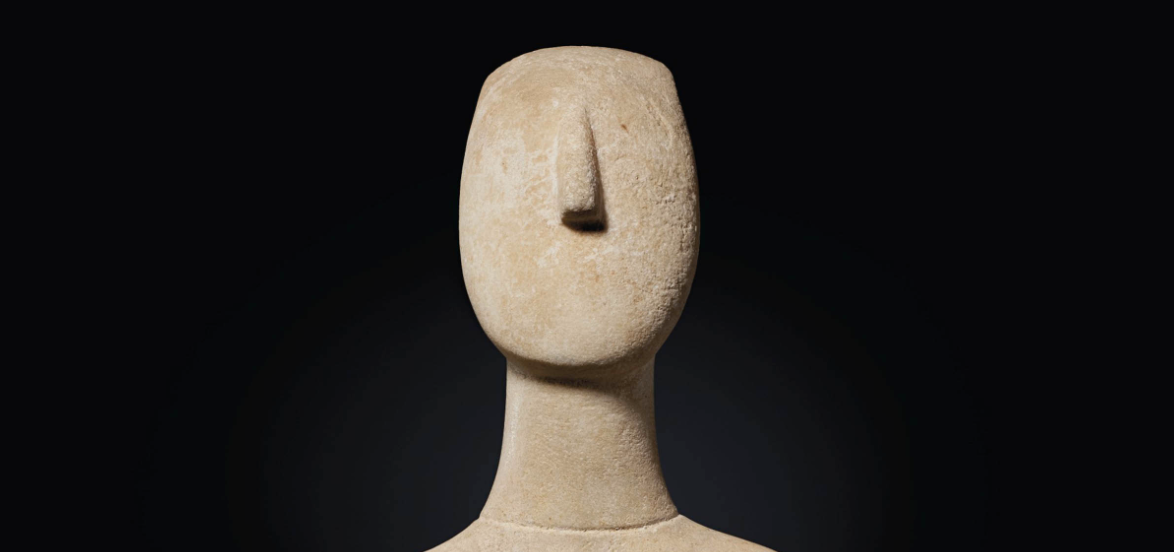

The greatest, most balanced and beautiful conception of the mask in all of history can be seen in the pure abstraction and balanced form of cycladic sculpture. Modern archaeology tells us that these sculptures were once not nearly as abstract as we now understand them, as trace evidence of pigments shows that these statuettes were once realistically painted; however, the understanding of cycladic art as pure colourless abstraction has influenced generations of artists and continues to hold a special place in the aesthetic tradition. As a person living in the modern world, I understand and interact with this art in the way it exists in the here and now, so I'm opting to ignore the fact that the people who made these statuettes would've disagreed. Abstracted to its most basic formal elements, the mask in cycladic sculpture shows maximum balance and economy of formal material. One way this manifests itself is in an internal grammar of opposition, with the semantic function of each element determined not by its own structural characteristics but by its relationship to the other elements present. Take a look at this image of the head of a cycladic statuette:

You could certainly say that that's a pretty shitty sculpture of a nose. It's all rectangular and plain, really it bears very little resemblance to my own shnoz. If presented with that rectangular piece of clay on its own, we certainly would not understand it as a nose; the same goes for the plain, stark, smooth, formless area around it. We would not understand that as the non-nasal portions of the mask, but most probably as a plain pebble, maybe mildly interesting in its smoothness and regularity. So why do we look at a cycladic statuette and immediately understand this maximally abstract form as a representation of a human face? Because of the way that these two basic elements are pitted against each other, delicately arranged with maximum care and purpose and balance so that their opposition gives them both individual and synergetic meanings: a nose and a forehead that make a face. A structuralist formal grammar that allows for the absolute maximum meaning to be derived from the most basic, abstract, and economical materials. Rather than using complicated, fancy materials, the cycladic statuette takes two exceedingly simple abstract elements and treats them with the utmost care and intention, creating an elegant and remarkably balanced final artistic product, without having to use vain, navel-gazing complexity.

This economy of material to prioritise careful, balanced use of the introduced elements is the fundamental principle of my aesthetic sensibilities. If there's one thing to understand about my aesthetic principles it's that I adore delicate, elegant, minimal, abstract forms, which gain their meaning from their opposition to what's happening around them. To me, this is what is so attractive of the music of György Kurtág, my favourite composer. Kurtág is the best miniaturist of all time, following in the tradition of Webern in writing exceedingly small scale movements (sometimes as short as only a handful of seconds) with a maximum economy and balance of material. Kurtág's miniatures are only as long as they need to be; there is no need for him to revel egotistically in his own cleverness, since his cleverness speaks for itself. Basic material is simple and abstract, no need for vain complexity. Forms are small and humble, textures delicate and balanced. His instrumentation is also humble and small scale: I love Kurtág because I abhor the orchestra and its vain opulence. A grotesque, bloated aberration of an ensemble, the orchestra, frozen in time for 150 years, is easily the most influential surviving symbol of gluttonous romantic excess. It's a cartoonishly absurd display of man's hubris: how highly must a composer think of himself to truly believe that his musical ideas are complex and important enough to require a hundred musicians to be properly expressed? How arrogant must a person be to really believe himself capable of creating a truly effective use of an ensemble the size of an orchestra? The orchestra is flashy, showy emptiness. It guarantees impressive effects and stark contrasts with no real skill required, but no human person could ever truly even come close to scratching the surface of what it means to truly effectively utilise the full range of its potential. Even the most skilled orchestrator could never achieve such a feat. It's pointless vanity through and through. Meanwhile, a person could spend just as much time writing a 5-minute piece for string trio as they could a 45-minute piece for orchestra, and the result of the chamber piece will invariably be orders of magnitude more intentional, thorough, and refined. Furthermore, in an era where gluttonous humanity has doomed us to a fiery demise in the furnace of climate change, surely we want to disavow pointless aesthetic excess? A simple, balanced, and economical music for a time where sensible, restrained use of what we have is more important than ever.

Now I'd like to turn away from the world of abstract representation to take a look at the way these aesthetics represent themselves in the real-world object that is the mask: the actual upper part of actual people's actual faces. At the cafe where I like to spend my mornings a couple times per week, there is a girl who does her makeup in the same way every day. Concealer as needed, winged eyeliner, subtle dark blush on her cheekbones to contour her face. She's very good at makeup, and she clearly has her style figured out. It's admirable! Sometimes she spices it up with some eyeshadow or glitter or whatever, but the basic elements remain the same.

Earlier this week I went in to get my coffee and there she sat, on her laptop, wearing just a little bit of concealer under her eyes and nothing else. I was struck dumb. I couldn't stop staring. Every time I tried to mind my own business and focus on my coffee, my eyes were drawn back to her features, carved like a Greek statue out of clear olive-brown skin. Stark, well-groomed brows, brow ridge melting smoothly into the strong bridge of her distinct aquiline nose, temples fading into her high cheekbones. I stared. I must have looked like quite a freak. And I wondered to myself, what exactly about this picture is so alluring and pleasing to me? The answer, I believe, lies in today's typical depiction of the female mask in the public sphere. There is an emphasis across our culture on 'snatching' features: adding contour, strong lines to further define your features, winged eyeliner to define your eyeline and draw attention upwards. This way of treating and depicting the mask (in media, in art, on people's real faces) is a form of hyperreality which has become so strongly engrained in our minds that to see a person's mask without any of that added definition is a very unusual experience indeed. In a world where this hyperreality has become the standard, a person's natural, un-altered mask can in fact be understood as a kind of abstraction of the hyperreal mask that we have come to see as the archetype of the form.

Now I want to be fully clear, I absolutely adore complicated makeup. This is in no way an anti-makeup take. I would say I leave the house 8 mornings out of 10 with the exact same kind of hyperreal, contour-augmenting full face, and I especially love winged eyeliner. In fact, the plain, economical reality that we recontextualise as an abstraction of the hyperreal is actually best achieved with just a little bit of makeup: a bit of concealer under the eyes to smoothen out the bags and darkness and create a sense of uniformity with the rest of the mask. In the context of a powerful, hyperreal internalised idea of the mask, the plain reality of a person's unaltered mask becomes a form of abstraction, achieving in our perception the same stark, alluring, balanced economy of material as a cycladic statuette.

The question I have yet to answer is what exactly to do with this knowledge -- do I capitulate to the hyperreality that permeates today's art and aesthetics, and focus on a sensible middle ground of abstraction and economy of form, knowing that in the context of our time it will have a comparable (and arguably more poignant) overall effect to that of pure abstraction? Or do I adhere to somewhat-outdated ideals of a music of extreme abstraction and restraint, knowing that the final product will be a more faithful representation of what I personally want to see in art? These are questions that I hope to answer through exploration in my own compositional work going forward.

These are some of the basic principles of my aesthetic! I hope I've cleared up some of the questions people have been asking me lately. thanks for reading, I'll be back soon with my regular blog content.

-A